Effective Marathon Training: HIIT and VO2 Max

Timestamps:

01:18:22 Introduction to Crissman Loomis, his background in mathematics, and his hobbies including body hacking.

01:20:59 Emphasis on exercise efficiency, optimizing health benefits while minimizing time and effort.

01:21:41 Details on respiratory training and VO2 max testing.

Q&A Session:

01:44:31 Question on Running a Marathon Again

01:45:46 Advice for Preparing for a Half Marathon

01:47:03 Managing Heart Rate During Long Runs

01:48:43 Correlation Between Training and Longevity

01:53:09 Nose Breathing vs. Mouth Breathing While Running

01:55:18 Importance of Strength Training for Longevity

01:57:39 Impact of Starting Exercise Later in Life

02:00:20 Effective Walking Distance for Longevity

Host - Okay, here we go. Doctors say exercise 150 minutes weekly without much detail. Going down to the cellular level of energy production gives a clear picture of how to improve cardiorespiratory fitness with less time but more targeted exercise. Crissman applied the latest research to his 16-week marathon preparation. He targeted a sub-3:30 time in his first marathon. That's, I think, pretty impressive. Well, I guess he'll tell us whether he made it. Learn the components of cardio exercise and how best to improve your fitness.

So, a little bit about Crissman. He is a mathematician by training and` a long-term body hacker, applying the latest research on himself. That's the way science is done, right? From a year of veganism to an intensive two-month strength training, he sifted through the latest studies to identify which interventions add the most years of life. And Google Scholar is his favorite bookmark.

And I don't know if any of you noticed—you'll have to tell me at the end of his talk whether you agree with me—but I think he looks like a skinny John Cena. I'm just putting that out there; you just let me know at the end of the talk what you think. But anyway, for now, put your hands together for Crissman Loomis!

Crissman - SEC, okay, yeah, you got your clicker? I have a clicker, and I go the other way; there we go. Uh, yes, it does. Oh hi; thank you for coming out tonight. It stopped raining, at least for you to be here. So, as I was introduced, I've been a mathematician by training. Uh, this is my site, actually. There we go, unaging.com.

So, I've been doing health and longevity research now for several years, but before that, I was doing more mathematical stuff. I was an AI programmer, so the AI topic is near and dear to me as well. But out of today's speech, and for coming to hear me, I want to make it clear that you don't have to run a marathon; it's fine. I'm hoping that I'll give you some information that'll be useful on how you could be more fit in your own lives and what it is that would make more of a difference for you in getting the best health from the least time. So, when I was doing the AI programming, my focus was usually on optimization and trying to find the way to get the most benefit from the least amount of effort.

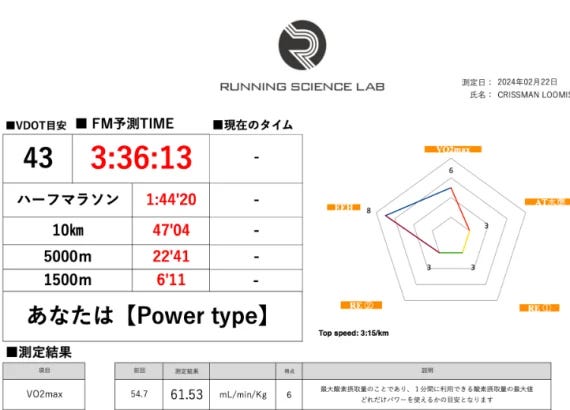

So, I came to the same approach I had been doing research on this for about a year or so, and I decided that I needed to figure out what my cardiorespiratory fitness was. For those of you who've done respiratory stuff or training before, VO2 max is a very important statistic. It is the velocity with which your body can convert oxygen into energy in one minute. So, I went down to actually there's a place where you can do this down in Otachi, the Running Science Lab. And they put a mask on your face that monitors all the oxygen that comes in and the carbon dioxide that goes out, and then they tie you to the ceiling in case you can't run as fast as you think you can because they just keep on boosting the speed until you can go no faster.

And it was an interesting trial. I was just doing it kind of just to see how I ranked, and I was very happy to see that I got quite a good ranking at 54.7 VO2 max, which is about 1 in 50 by age. And they said that with that kind of my other measurements as well, that I could finish a marathon in about 3 hours and 34 minutes. I was really happy about this because then I could just say if I were to run a marathon, that's about how long it would take. Because I've never run any race. I did the Spartan races, about the closest thing, and that was about a decade ago. So, for a long time, I just said, 'Okay, well, I mean, I could run a marathon, but I'm busy.'

But then, as time went on, I kind of thought, 'Okay, well, could I?' And then I had some friends who said, actually, 'Look, we're going to run a marathon in Osaka, and it's for charity, and we're all going to do it together.' And so I thought, 'Alright, it's time for me to actually find out whether my research and thinking about this is effective or not.' So, this is backing up on what I've been doing up until that point.

So I've done a lot of my research based on actuarial tables, and all-cause mortality tells you, basically, what your chance of premature death is. So I run through actuarial tables and I say, 'Okay, if this has an all-cause mortality reduction of let's say 75%, what does that mean? How many more years will you actually live?' This is the answer. So, walking or high-intensity interval training will reduce your all-cause mortality, both of them, by around 75%. And at the age of 50 for a man, that will mean you live basically 10 more years of life, on average, expected.

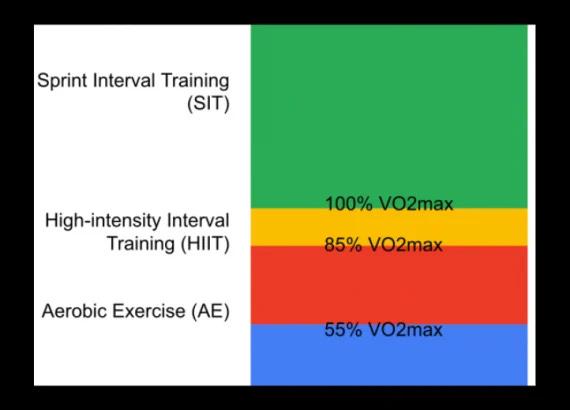

And I found it very interesting—high-intensity interval training, the one in the middle here, is actually the one that's most relevant for the marathon. This is dealing with high-intensity intervals, so you run full speed, 100%, for a dash for maybe a minute or two, and then you kind of jog to keep up and then do it again. So you do several intervals of this. And I had been doing this already for about two years, which is why I think I had pretty good VO2 max to start with.

But if we look at how that fits, then, how that fits with the other kind of aerobic exercise you can do, you can see here this is as a percentage of your VO2 max. You could also think of this as your maximum heart rate if you're more familiar with that. But aerobic exercise is basically exercise where you're breathing hard. You wouldn't be able to speak normally or sing a song, and that's at about 55% VO2 max. And then the high-intensity interval training, so when you're running full out, is between about 85% and 100% VO2 max. And at this range, you wouldn't even be able to speak a sentence without being out of breath. And when I do the VO2 max, I run for about one or two minutes and after that, I'm just gassed. I can't go any further.

So I've been doing this already, but as I came towards the marathon, I was thinking, 'Okay, well this again is looking at the benefit that you get from your aerobic exercise versus your high intensity.' And the aerobic exercise is actually kind of the lower amount, as you can see like you get about two and a half years or so of extra life from the aerobic exercise. But there was an excellent study that was done, I believe in Norway, that took people who are 70 in their 70s and had people who were already doing a lot of aerobic exercise, they were already doing 150 minutes of aerobic exercise every week, and said, 'Okay, now do that plus high-intensity interval training.' And they found that the years gained was about another 7 and a half years. So the high-intensity interval training really gives a much greater benefit in your VO2 max than just doing the aerobic sort of steady-state things.

So I've been doing this for a while, but I was still quite nervous about how the marathon was going to go.

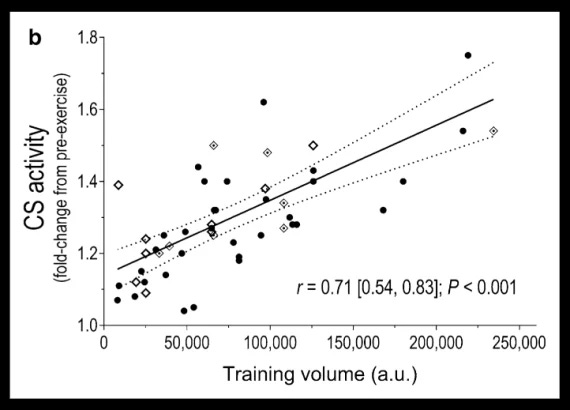

So, one of the things I looked at was, 'Am I ready for this?' And so this chart is a bit busy here, but the thing that is important is that it's basically just a linear line here, and the units along the bottom are arbitrary units, but basically, this is the total amount of time that you've been running, assuming you're running every week, and the units on the vertical axis here are your CS activity, which is your citrate synthesis improvement on your mitochondria. None of this will be on the exam, but basically, this is how much your VO2 max has improved. So the point of this is that basically, the more total time that you've been running, whether it's over one year or whatever, the more your VO2 max has increased.

So this I found to be a little bit surprising because I thought if you ran like three times a week, you would get better faster or something, but basically, if you've been running consistently over a long period, you're already going to be pretty much up towards the maximum of what your VO2 max can improve. Okay, so then I think, 'I'm ready to start training for the marathon.' So the next thing that I do then is I buy myself some very fast shoes. Uh, research, so um, this wasn't Google Scholar, this was the Boston Marathon fastest shoes worn by the top 200 runners in the Boston Marathon last year—the Adidas Adios Adizero Pro 3s. You can buy them in Shibuya at the Adidas store. So I bought a pair of those; they're the carbon fiber ones that are on the borderline of being banned. But I didn't think that was quite enough.

So the next thing I did was then post that onto a prediction website. Okay, I wanted people to tell me, 'You won't make it,' and then ask them why, so I could know what I needed to do. So this is on Manifold, it's a funny money website, although they're converting and other things, but it's a website to say, 'Okay, will I be able to make it in under three and a half hours?' And I gave them as much information as I could so they could tell me why I wouldn't make it, so I could take care of it, and I listed that I'm diligent, I work hard, I'm a health and longevity researcher, I ran the Spartan Race 10 years ago and finished in the top 10%, but I also wrote what are the reasons that I wouldn't make it, right? So the reasons that I don't think I might make it is one, this is the first race of this caliber that I've ever run, second thing is I'm already over 50 years old, and lastly, I'm really only going to run three times a week. I'm not a runner. I think I'll just run three times a week. So, a number of people put a lot of money against me saying, 'No, I don't think you're going to make it.

Which one of these three do you think they thought was the thing that was going to keep me from making it? First, first one there. One, anyone going to guess a second? Anyone? Second, there we go. The answer was of all the runners that I talked to had done it, it was the third one. They're like, 'You're just not running enough.' They were like, 'I mean, yeah, okay, you haven't run a marathon before, that's a little bit of a bump, there are some things you need to learn. The age can be dealt with, but you need to be running more than three times a week.'

But, well, here's what a typical marathon training plan looks like. It's a lot of running. I'm not sure I signed up for this. They run every day for about an hour a day, and many of these runs are kind of—they have some of them in here that are like interval kind of training, which is more like the HIT thing that I think of. Some of them are what I would say is a long-distance run, where you're running just to get used to the distance of a marathon, but the blue ones here, a good number of them are kind of like, 'Oh, look, just go out and run. You just need to be running this, do an easy run, just keep doing that running thing.' So, as I looked at this, my theory was that I don't know if these are actually improving anything. It felt like this is kind of just putting in time. So, I Googled a bit further and I found the 'less is more' program that would support my intention to only run about three times a week.

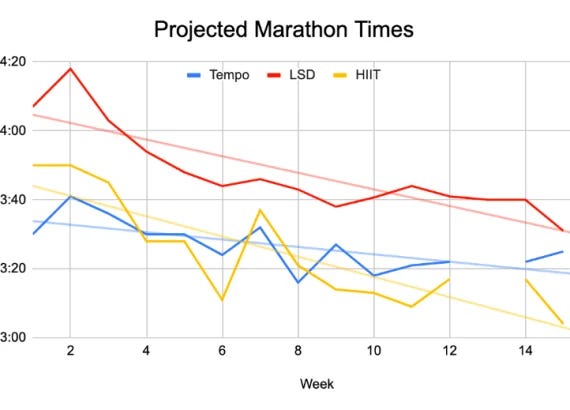

So, the 'less is more' marathon training plan was used by someone quite successfully to run a marathon, and in using this, they were able to run just basically three runs a week, and each run was very focused. So, they had one run which was the tempo run, between say 5 to 10 km where you just run the whole thing as fast as you can, good luck. And then they had interval training, is what the running world calls it. I call it high-intensity interval training, which is where you're doing wind sprints for a minute or two and then doing a jog, and then a wind sprint is the second run. And the third run is what they called long slow distance run, and the idea is this to get your body used to the distances that you run in a marathon, which is quite long. So, every week I would run one of each of those runs, just three runs a week, and I would track them diligently, of course, in Excel.

So, this is using a formula called the Regal formula. With the Regal formula, you can basically put in, 'Okay, I ran 10 km in 42 minutes. So how long will I run a marathon?' It does an extrapolation based off of the distance that you ran and the speed that you ran it in and can give you an estimation for any other distance. So, I took all of my runs and then plotted them, uh, from week to week, one all the way to week 16. I did a 16-week training plan to say, 'Okay, given the speed that I ran it at, how fast would I be able to run the marathon at that speed?' And, fortunately, you can see it's getting steadily better over time. I consider the tempo run, which is like about 5 to 10 km as fast as you can, to be the best indication, and you can see that I started out at about 3:36, that's right about right, and then steadily decreased with a bit of a flattening here towards the end, uh, to the point where it said I could run in about 3:20 towards the end. Um, and this gave me a lot of confidence as I could see, okay, look, I am getting faster even though the distances and the times would be changing throughout the thing, throughout my training experience.

But even so, with that, I knew that there was something coming, um, because there was still that second line of, uh, or first line of, 'Have never run a marathon before.' One of the things they tell you in a marathon is that uh, you should do nothing new on race day. You should wear the same shoes, you should have the same wake-up program, you should have the same breakfast, you should have done all of that in advance so that nothing surprises you when the big day comes. But they say that even though the one most important thing is always going to be new, which is that you never run a marathon before you run a marathon.

So, when I talked about doing long slow distance runs, that's still the longest long slow distance run, this is building up over 16 weeks was only 26 km, uh, sorry, 21 km, and that's only half of a marathon distance. And at first, I was kind of like, 'Well, why don't you run a full marathon to practice for a marathon?' And the answer is that marathons are exhausting. So, I could run like a 10 km at full speed, Temple Run, take me about an hour, and then I'd be tired, but I'd get over it, and I could go out and have meet with people and do things and be a functioning human afterwards. But the two-hour runs, like the long slow distance runs, I would be flattened afterwards, and it would be like a like the rest of the day, I was just kind of laying around and kind of moving slowly, and even the next day I would still feel slow. That's only half a marathon. So, they don't ever have you run the full distance of the marathon before the marathon because then you wouldn't be able to keep up your training plan, you'd have to take like a week or at least a few days just to recover from having practiced.

So, I knew that there were things that happen in a full marathon that don't happen during the training. They say that the marathon's basically two marathons, there's the first half, which is the first 30 kilometers, and the second half, which is the last 12. Right, and they talk about in the second half that's where you hit the wall, all of a sudden it's kind of like, you've been keeping your pace, you've been doing it as you want to be able to do it, but after that point, your legs feel like they're lead, you just don't feel like can go anywhere, and people talk about how they were running great, and then at that point, they walked until they could get a banana and ate the banana and then kind of recovered and stuff, but they lost a lot of time. So, I was really worried about this because I, I mean, I think at the times that I was doing, you could see from the charts there was saying that at that time I should be able to run that period, but that's not with the break in there where I walk for a period and, and look for a banana.

So, I started to do some research on that, and I found this paper that basically said there were two kinds of approaches in the study. One group was the 'freestyle' group, where people basically ran the marathon how they wanted to—they drank as much as they wanted, they ate as much as they wanted. The other group followed the 'scientific method.' This group ate the prescribed amount of food and drank the prescribed amount of water. And the prescribed amount is they said, 'Look, you need to get 1,000 calories in the race from gels, right? So you need to be eating about 25 grams of carbohydrates every 15 minutes.' That’s quite a bit.

So in the marathon, then, I was practicing doing the scientific method. And so I had a belt that had elastic around here and I had 10 gels strapped around it like a bandolier while I was doing my practicing for this because, as you can see here, basically they start out the same, the scientific and the freestyle, but as I was talking about, it's right around kilometer 35 that the running velocity of the people who didn't have the extra carbohydrates in the race starts to drop, and they recover a little bit for the last two kilometers as they can see the finish line ahead of them. But basically, this is the cause of the wall. And when you read the study, it's kind of funny because you can almost hear the scientists' tears as he says, 'It is unclear why amateur runners do not eat sufficient carbohydrates when they're running.'

So, I decided I was going to do it. Other things they talk about — they talk about carb-loading as one way to all this, like the day before the marathon, you should eat a lot of spaghetti and pastas and things so that you absorb as much carbohydrates as possible in your muscles. But I found another study that talked about doing a comparison between people who had breakfast and didn't have breakfast and did carb and ate gels in the race and didn't, and they found that the worst group was the group that had no breakfast and had no gels. Okay, the second worst was the group that had breakfast but didn't have any gels. And then if you had gels, you took calories during the race, then it didn't matter whether you had breakfast or not; they were both the same. So the most important thing was to take the calories directly during the race and practicing with them as well.

So, in the 'nothing new on race day,' I was practicing when I did my long slow distance runs as well, to take gels. So then we come, uh, next to the race, and I'm thinking, 'Okay, well let's get a retest here. Here's my previous test before. Okay, should finish in about 3 hours and 34 minutes.' So it's one week before the marathon; I've been training for 15 weeks now, I'm going to go in and get my VO2 max measured again. And so I go in there and they put on the mask again, and they chain me to the ceiling, you know, rope me to the ceiling again in case I fall down, and they say, 'Well done, sir, we think that now you could run the marathon in 3 hours and 36 minutes.' I'm like, 'Okay, now you're just fake science, now I don't believe any of it.' They actually said that my VO2 max had gone from 54.7 to 61.5; this is ridiculous, this is one in 300 level by age. So, I decided I believed this part but didn't believe this part.

The other measurements they use here, you can see there's actually a grid, and it's a bit detailed, but they're also looking at your anaerobic threshold and also the running economy. And they said yes, your VO2 max got better, but they said your running economy got worse, and your lactate threshold got worse, so we don't think you can do it. And I said thanks. But the other things vary a lot more, so they're saying maybe you had a bad day today, maybe you're overtrained or something.

So then, I thought, 'Okay, well, we'll see how it goes.' Anyways, the marathon's set, I'm still going. Here I am down in Osaka, and get ready to go, and start off, and I'm keeping really strict time with my watch. One of the other things I had heard a lot of people who had done the marathon, who had had trouble, was that they started out too fast at the excitement of the moment or whatever. So I had already knew what my pace was, wanted to do in order to make the three and a half hours, I needed to be under about 4 minutes and 45 seconds per kilometer. So I had my watch set, and every time I went 5 seconds faster than that, it would tell me to slow down, if I was slower than that it would tell me to speed up, and I tried to keep that as close as I could.

And that worked great until kilometer 38 when my watch died. It's fine, it's a 42 km marathon, I just was in blind mode from that point. And here you can see the joy and exaltation of running a marathon clearly all worth it. That's my runner's face. I think I was very in the top 1% for runner's face. But here's the actual results and the bottom line is that I finished it in 3 hours and 26 minutes, first marathon out of the gate. I was quite nervous about it; I was very proud that my times, as you can see, like every 5 kilometers, I'm hitting it about 24 minutes and change each of the kilometers, and I didn't hit the wall, or there's no appreciable slowdown here even as I got to 40 km. Also, you can see that like my ranking here is about 260, about 260, and then at this point is where I start to pass some of the other people I'm running with, another 36,000 runners. So I had to do a lot of weaving to get through to that, but it really was validating for me to say that the science actually does work. I don't just have a paper, but by applying the studies and the other things, that really can make a difference in performance.

And so I want to let you know that I am doing a 2025 health for life challenge, so I already have some people, and after I finished this I had a friend of mine who said, 'Okay, thank you, I'm inspired, I've been reading your blog but I haven't actually done anything on it the entire time.' So now I want to do a program so that I can walk up a flight of stairs without being out of breath. So we're now on week seven of our first trial of this, and his VO2 max is already up by about 8%, and he can now walk up a flight of stairs without being out of breath. So I'm recruiting people who are interested in doing a program for improving their health. We'll start this in 2025 and work through the optimal amount of exercise thatyou need to do to be as healthy as you can be but all the information is on my blog at unaging.com. I have articles there on Brian Johnson in case you've heard of him, he's another health guru. Benefits of alcohol, maybe this is, uh, you can guess my answer for this given I'm here tonight, limits of human lifespan, and also as we're heading into summer, sun health advice and a lot of other things.

So, that's my talk. Thank you for listening and uh, if you have any questions, I'd be happy to answer them now.

Question 1:

Participant - Sweet thanks, hi thanks for your talk. I have two questions. One, um, do you think that you are crazy enough to run a marathon again?

Crissman - It's not actually healthy. I mean, it's a little bit Nutter Butters but yeah, I think it's... I'm putting it in kind of... I mean, that's one of the reasons why I had never planned to do it in the first place. It's beyond the healthy barriers, but I consider it to be kind of like climbing Mount Fuji; it's a great thing to have done once. I took a health test during the middle of that too and the results were not good. My heart stress level was very high, my testosterone was below the normal bounds, and my liver enzymes were all over the top. Then two months later, I took it again, my testosterone jumped from below the barrier to above, the liver enzymes were all fine, and I think my heart is fine again. So, I mean, I can't say never. I didn't think I'd do it this time, but I think I want to focus more on the healthy level for a while.

Participant - Yeah, that sounds sensible.

Question 2:

Participant - I recently agreed to doing a half marathon before I could say no.

Crissman - Okay, um, I know how that goes.

Participant - Yeah, I just said yes as quickly as possible and have been trying not to think about it but I've been, you know, working towards that. Do you have any... what would be your advice based on your experiences for someone else who's getting into this? You went through a lot of different things. If you could boil it down to the best advice for somebody that wants to do something half as crazy as you did, what would you say?

Crissman - Well, the good news is you don't need to worry about hitting the wall as much because that happens in the 30 to 42 km range. For the half marathon, the key things are going to be similar: doing a slow distance run. The slow distance is run deliberately slower than you could. So I learned actually more about that as I did my training. One part of it is what they call Zone 2 or Maffetone training where you just do the long runs for slow times. The nice thing about doing a half marathon is actually you can do it without killing yourself in the training. So I would stick with those three primary runs as the foundation and then maybe add more if you feel like you want to run more.

Participant - Great, thanks. I'm on two runs a week, we're going to stick with that for a while.

Crissman - Okay, any other questions?

Question 3:

Participant - Sorry, so I noticed you didn't talk so much about heart rate but I do notice that, you know, if I tend to keep at a certain tempo for a sustained period of time, my heart rate tends to go up even though I'm keeping the same tempo. Is there anything that kind of helps with that? I'm not sure like what kind of training kind of helps with not, you know, increasing the heart rate till it reaches kind of your max heart rate?

Crissman - It's called cardiovascular drift, that's the technical term, and it is just something that happens. When I did the first VO2 max test and I'm tied to the ceiling and they're hitting it as fast as I can for like 15 minutes, at the time I thought my maximum heart rate was around 170. But then when I did the marathon training, where I was running for an hour and a half or so, I found out no, my heart rate can get up to 190, which I've never hit since either. So it's just one of those things that you need to be ready for, I'd say more than preventing. But the Zone 2 kind of exercise, where you're doing a long slow run and deliberately breathing through your nose, is a good way to sort of put the brakes on the heavy breathing. If you can't breathe through your nose, then you're running too fast and you should slow down. That is one of the ways that you try to train yourself to do the same amount of effort but with a lower heart rate. But it is one of those things you just... all the heart rate things that I saw during a marathon or a longer race showed that kind of a slow drift upwards over time.

Participant - Cool, so work with it.

Crissman - Thank you.

Question 4:

Participant - Alright, we got some other questions out here. Oh, right there and, um, thank you very much for the talk. This is, um, congratulations.

Crissman - Thank you.

Participant - Unfortunately, I am not a runner. I prefer cycling but I cycle a lot too. So my question is, you mentioned that the training that you did and the research you did is more about longevity. Do you have any... because for longevity, it's nice to live a long life but it's also kind of useless if you are not healthy, if you are not mobile, if you are not capable of independent living. Do you have any data that shows correlations that these kinds of trainings, aerobic or high-intensity interval training or other types of training, have any correlation with the improvement of quality of life for people who are above 70 or 50, or senior citizens, let's call it that way?

Crissman - Right, so that's often times called health span as compared to lifespan, right? So how long do you live free of any comorbidities or frailties or other things. There is good research on this that basically says that if you're increasing your lifespan, for the most part, you're also increasing your health span. It's about the last five, 10, or 15 years or so, but it's pretty much a straight percentage. About 80% of your life you can count on being able and well and able to do whatever you want. So if you increase the number of years you have, you're increasing the number of healthy years that you have as well, about 80%. And that's generally true. One of the exceptions to that, unfortunately, is BMI, which is one that if you have a higher BMI... BMI is a measure of how much you weigh per your height. So if you're more heavy weight, even if it's muscle, whether it's fat or muscle, then that actually reduces the health span versus lifespan ratio. But aside from that, basically, as long as you're increasing your lifespan, then you're going to be increasing your health span as well.

Participant - Okay, so does the training also... can the training make your health span go beyond 80%?

Crissman - It can only increase your total lifespan of which 80% will be healthy. Does that follow?

Participant - Okay, it does.

Crissman - These exercises I had in the first chart, the high-intensity interval training increases your lifespan by about 10 years in and of itself, so that would give you eight more healthy years, maybe two years that were not as good.

Participant - Okay, do we know if there are any causal links or pathways between VO2 max and longevity?

Crissman - Yes, it's directly correlated. Peter Attia and several other people have written quite a bit about it. It's actually one of the best predictors for overall lifespan is VO2 max directly, and they find that there are improvements in being in the second quintile versus the first quintile, the third versus the second, all the way up to the elite. The top 2% live significantly longer than the people in the top 20%. So VO2 max is highly correlated with overall longevity.

Participant - But do we know like any causal reasons behind this?

Crissman - I'm a mathematician, not a doctor, so I deliberately avoid causal arguments because I don't think we really know them well enough. If you focus on a cause, oftentimes then you can say, therefore this will kill you, and you might miss this other thing that makes you live longer or the reverse, where you say, oh, this will make you live longer but it could have another effect within the body. The complexity of the body is insane. So, no, I don't know exactly how. I think it has to do with the cardiovascular very heavily and in the older years that goes up exponentially faster even than cancer. So I think it's basically giving you more ability to get the blood where it needs to go. But as you can see, I'm getting somewhat less scientific here as we get to that theory.

Question 5:

Participant - Oh yeah, I have a question about mouth breathing versus nose breathing. I find it very difficult to maintain nose breathing after a certain pace of running. It seems that once you drop to mouth breathing, your VO2 max will just tank. So are there techniques that you can do to improve nose breathing?

Crissman - The technique is to run a lot slowly. When I talk about doing that deliberately, it's to stop yourself from running too fast. Interestingly, high-intensity interval training is the central respiratory system—your lungs, your heart, and the mitochondria, which are the organelles in your cells that convert oxygen to energy. But the long slow distance is actually running and working the peripheral system, so it's increasing your capillary density and other things. High-intensity interval training is a fast hit, unintentional pun. It works very quickly. If you do it for a month or two, you can get quite a bit of a gain in your VO2 max. The flip side is if you stop it for a month, it disappears fast as well. But the long slow runs take a lot of time. Lots of runners have long periods of years running several hours a week to build up the cardiovascular respiratory system. Most of my gains were probably from the long slow runs as opposed to the high-intensity interval training because I'd already been doing that, but running for two hours at a slow pace was quite new for me and that's probably where I gained most of my benefit from. But it's guesswork, though.

Participant - Thank you.

Question 6:

Participant - In the years gained chart, I saw that strength training is not quite as effective as the high-intensity kind of training and walking. But I've read that some researchers put a heavy focus on strength training because as you get old, the risk of falling and losing balance increases. And for that reason, not having enough muscles is dangerous. What do you think about that line of thought or idea theory?

Crissman - It's definitely true. Sorry, your headset just died. Okay, but the thing is, the other things are giving you more... I mean, strength, if you look at it this way, this would be more than having three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruit every day. So a two-year increase in life is quite significant. So what you're talking about, reducing the chance of falling and other things and having strength, is quite important. It's just that the other ones are actually even more effective. I'm not sure if that really answers the question. I believe in strength training, I do it every week, it's going to be part of my Fit for Life 2025 challenge, but it's not the first one or the most effective.

Participant - Okay, we've only got one mic now.

Question 7:

Participant - Thank you for the great talk. I'd like to ask about this decrease in mortality that you're talking about. If I can make it to like 60 without exercising or doing anything, and then at 60 I do all your tips, I've decreased my mortality, right? Are all my years gained going to be equivalent to someone who's been exercising their whole time?

Crissman - I've thought about this too. The ideal thing, honestly, is the day before you would have died, start then exactly. I do believe that the system doesn't have memory in it. I don't bother telling this to college students. Well, I mean, I tell them, but I don't keep it secret. But I don't think that it's as important at a young age to start doing this because your chance of dying of cancer or cardiovascular disease or other things when you're young is tiny. It's minuscule. So I definitely think it is something that as you get to a higher age becomes more important. Many of these studies are based off just that where they took, I think the strength training one for example, I think it was based off a study of 60-year-old women who started lifting weights and were able to reduce their all-cause mortality at the age of 60 by 25%. So it is just one of those things that you do need to start before you die, but I don't think it necessarily is required that you start that much earlier. Although some of the things like cancer might be long developing, I think that is quite reversible and has the ability to do that. The other challenge though, of course, is once you're 60, are you really going to be that good at changing your habits to take advantage of it?

Participant - Thank you. I'd like to ask another question. I think in week 13 you dropped two runs. I'd like to ask what happened?

Crissman - I dropped no runs. That week I was in Nara skiing, so I did those exercises inside on a gym treadmill for the first time in my entire time. And boy, let me tell you, I sucked at the treadmill. But as a result, I didn't have a reliable time that I could enter, so that is a blank there on the tempo run just because it was an inside run as opposed to the outside runs in the other times.

Participant - Good eye.

Crissman - Thank you.

Question 8:

Participant - One more I can take. In that case, the walking seemed really valuable; it was the one that added the most number of years. How much do you actually need to walk to get that? It seems like a simple way to add years to your life, it's not so exhausting.

Crissman - So you're talking about the years gained from walking? Yes, I've done the analysis on the payoff for time as well for this. This is based off of 12,000 steps a day. It is diminishing returns, so the first 8,000 steps will get you, I think, three-fourths of this or so. Then 10,000 steps is kind of the standard, will get you another maybe 10-15% or so, and the last 10% is from the last 2,000 steps a day. This is actually what I consider one of the big opportunities in overall health. If you read many of the experts, Peter Attia, Dr. Greger, Bryan Johnson, they're great on strength training, in fact, they overdo it. But they do the high-intensity interval training as well, but many of them completely neglect walking because this just takes raw time and it's kind of not sexy. This is an hour and a half to two hours a day of walking. I cheat, I have a walking desk at home, so I'm doing my computer programming and I'm walking for four to eight hours a day. But it is easier here in Tokyo at least, you walk around to the stations and things. But it is a chunk of time, but for every minute that you spend walking, you get two extra minutes of life. So it's, at the same time, the easiest of the three, least effort, but requires the most time commitment to get the benefit out of.

Participant - Okay, thank you.

Crissman - Alright, so, big thank you to Crissman.