Unlocking The Physiology of Marathon Training, VO2 Max, Health, and Longevity

I did my third podcast on Conquer Aging or Die Trying!

Timestamps:

00:00 Designing an Effective Marathon Training Program

06:08 The Relationship Between Exercise Intensity and Mitochondrial Activity

11:14 Avoiding the Wall: Taking in Calories During a Marathon

16:36 The Effects of Marathon Training on the Body

36:29 Maximizing VO2 max and its Impact on Longevity

44:18 The Importance of Strength, Flexibility, and Balance

57:55 Consistency and Efficiency in Exercise

01:03:01 Conclusion

Links

Previous discussion, Podcast #1

Leisure-Time Running Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Risk https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0735109714027466

Training-Induced Changes in Mitochondrial Content and Respiratory Function in Human Skeletal Muscle https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29934848/

Improved Marathon Performance by In-Race Nutritional Strategy Intervention https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24901444/

Inter- and intra-individual variability in daily resting heart rate and its associations with age, sex, sleep, BMI, and time of year: Retrospective, longitudinal cohort study of 92,457 adults https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32023264/

Heart rate variability with photoplethysmography in 8 million individuals: a cross-sectional study https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33328029/

Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mortality Risk Across the Spectra of Age, Race, and Sex https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35926933/

Mean nocturnal respiratory rate predicts cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in community-dwelling older men and women https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31151958/

Meta-Analysis of Quantitative Sleep Parameters From Childhood to Old Age in Healthy Individuals: Developing Normative Sleep Values Across the Human Lifespan https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15586779/

Transcript

Mike: Hey everyone, today we've got Crissman Loomis on again for round three of our Conquer Aging or Die Trying series and unaging.com, Crissman's website podcast. So today's agenda will focus almost exclusively on exercise starting with Crissman's marathon training and then cardiovascular fitness metrics and a whole bunch of other stuff. So what have we got? Let's start it off, Crissman, and welcome.

Crissman: Okay, thanks. It's great to be here. Glad to be on the podcast again. So, as we talked about in the previous one, I've delivered on my threat of running a marathon. I did quite a bit of preparation for it. I went through a 16-week training in order to get myself in shape, and I was already doing some exercise. So I thought the first thing that would be interesting to talk about today would be how I designed, based off of my research, the overall program that I used for the marathon training and eventually get to how the marathon actually turned out.

When I started doing research initially on longevity and the best way to live as long as possible, I came across the governmental recommendation that you should exercise for around 150 minutes per week. I always found that to be kind of very vague. It sort of felt like they were saying, well, it's a really good idea if you want to live a long time that you should eat food, and we recommend you should at least eat 2,000 calories worth of food because people who only eat 1,500 calories worth of food don't live as long, right? It's very general. As I looked at the specific sports you could do, I found the same kind of generality. It wasn't really clear that just more was better. Some sports, if you did more of them, you didn't get the benefit as much, and some you did, and it didn't even seem like it had a pattern.

So I decided to simplify that and look at what I considered to be the most pure form of exercise, which is straight-up running or jogging. The studies on that are fairly clear. They show that they're fairly clear and unanimous, but in a surprising result. So let me bring that up. Basically, if you look at the exercise of what you get when you run, the running studies generally show that if you run on a weekly basis at all, for at least 15 minutes or so once a week, then you can see that very quickly you get a reduction in your all-cause mortality. This is a reduction in your premature death.

Mike: Hang on, Crissman. Share screen, because I don't see it on my end. Thanks.

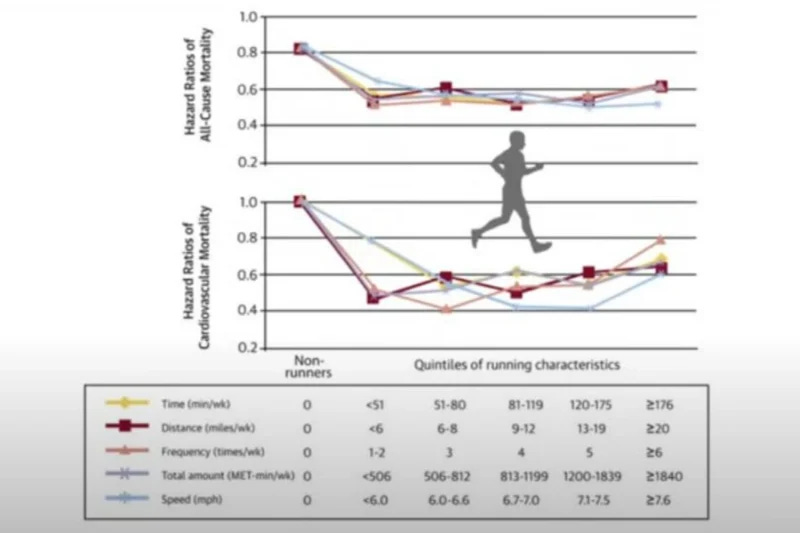

Crissman - Okay, there we go. So, if you look at this chart, this is showing the hazard ratios of all-cause mortality, and basically it's showing you how much it's reducing premature death by. As you look at this, as I was saying, you can see that as long as you're doing at least some exercise on a weekly basis or more, you have about the same 40% reduction, so a 0.6 hazard ratio for premature death. That seems to be consistent whether you're doing exercise once or twice a week, all the way up to over six times per week. And as for the speed as well, even if you're just doing a light jog at less than 6 miles an hour or if you're going over 7.6 miles per hour, again, it seems that once you've started doing any exercise, as long as you're not in the non-runner area, whatever quintile you're in, you get about the same benefit out of it.

This confused me quite a bit. I had seen other people, and we'll talk about it a little bit more later, who said that basically the fitter you are, the longer you're going to live. It's counterintuitive that even if you run more, you're basically not going to get any additional longevity out of it. I puzzled over this for a long time, trying to see how do these two things fit together, how can I make a complete image out of this. Taking a look at the speed that you run at, I thought that basically the faster you ran, the more fit you would be, and therefore the longer that you’d live.

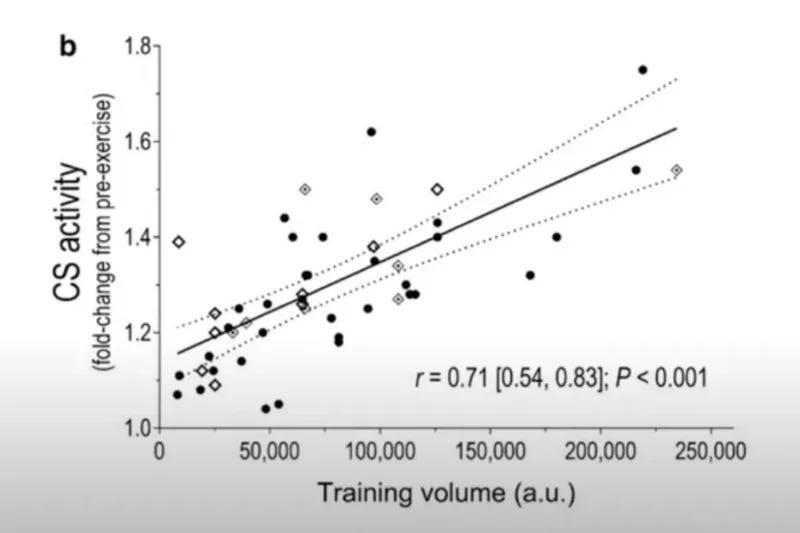

I came across a study specifically on mitochondria and how it adapts to exercise. Here's one of the important tables from that study, and this is talking about basically the increase that you get in mitochondria from different exercise intensities from bicycling or running.

Mike - Wait, just so I can add a little bit of context. CS is citrate synthase. That's a protein localized specifically to mitochondria. So if you have lots of citrate synthase (CS) activity, that's a marker of mitochondrial mass. Sorry.

Crissman - Exactly right. This is showing basically how much your mitochondria are increasing. To take another step back, mitochondria are small organelles in all of your cells, and it's where pretty much all of the energy of the body comes from. Any increase or benefit that you're getting from increased aerobic fitness is coming from increased mitochondria that then give you the ability to create more energy.

As you look at this, though, on the bottom we have the relative exercise intensity, and you can see that from a relative exercise intensity of even 40% all the way up to 100%, basically there's no increase in the amount of CS activity or mitochondria creation. This is saying that it doesn't matter whether you're going very hard and going at, say, 80% of your maximum heart rate or whether you're going at, say, 60%, it doesn't increase the mitochondria that much more comparatively for the overall time.

Mike - There's a weak spot in that, only focusing on the CS activity. That would be an indicator of mitochondria number, assuming that CS activity is proportional to mitochondrial number, but it's not a measure of mitochondrial efficiency. How well or how poor are mitochondria able to convert NAD and FADH into energy?

Crissman - You're ahead of the script there, Mike, unsurprisingly. Let me catch up to that in a minute. Let me jump to the next table from that same study. The next thing that it does is it takes the CS activity and now it sees how it varies compared to an arbitrary unit of training volume. To clarify, they take the total time that you spend, the total number of weeks, and they multiply that by the number of minutes per time. Then they further multiply that by the training volume of the intensity that we saw in the previous slide. If you were training at, say, 60%, you wouldn't be getting as much CS activity as if you were training at 90%, but if you were training longer at 60%, you might get even more CS activity. As you can see from the chart here, basically it's linear. The more total training volume you put in, the more mitochondria that you develop over that time.

[caption id="attachment_3371" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Scatter plot showing the relationship between training volume and citrate synthase (CS) activity increase from pre-exercise, with a positive correlation indicated by a trend line and confidence intervals[/caption]

This is saying that the difference between running three times a week versus running once a week is that either one of them will steadily increase your number of mitochondria or your overall fitness, but running three times a week will do it three times as fast. Eventually, within a year or so, you're going to come to the maximum amount of mitochondria that your body will sustain. This then is answering the question of why it does not matter whether you run five times a week or once a week. As long as you're running consistently every week, in the long term you're going to hit the maximum that you can within a year or so, actually probably quite a bit less than that.

Mike - There's another variable here too, to square the circle. Is there published data on citrate synthase (CS) activity and all-cause mortality risk?

Crissman - Citrate synthase activity, basically the number of mitochondria, is about 90% correlated with VO2 max. This is a secondary thing, so we're looking at how it's related to the mitochondria itself, but it's highly correlated with your overall ability to create energy and your cardiorespiratory fitness.

Mike - Cool.

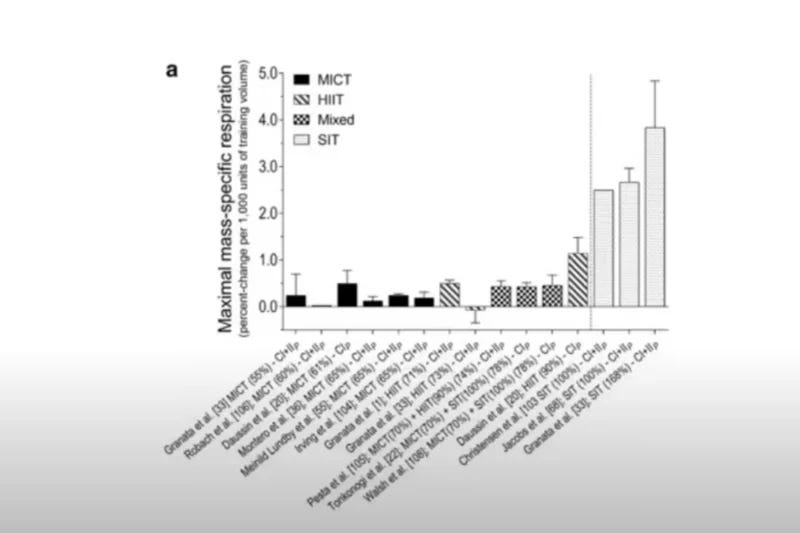

Crissman - I haven't got a direct CS activity to mortality, but a 90% correlation between this and VO2 max. As we know, there are studies that talk about VO2 max and mortality. To come back to your other point, the next table from this same study that's talking about mitochondrial activity, now we're talking about the maximum mass-specific respiration. Honestly, it's a label that every time I read the study, I've got to think over it again to figure out what it means.

But basically, this is talking about what you just said, Mike. This is talking about the efficiency of each mitochondrion. As you increase the number of mitochondria, you increase your overall ability to create energy in each of your cells. But there's another measure here, which is to say how efficient each mitochondrion is. The mitochondria actually have a very short lifespan within the cells; it's between 3 to 10 days half-life. So they're continually being decommissioned and recreated over time, and many of them can lose efficiency. Just like your car wears out, the mitochondria, even though they have a short lifespan, eventually lose efficiency. But if you push yourself really hard, then you increase the efficiency of the mitochondria you have as well as increasing the number.

So, this table is showing you the efficiency of the mitochondria. We have moderate-intensity continuous training, which is just a steady-state aerobic run, say, jogging at a steady pace; high-intensity interval training, where you're running full out and then doing a low jog or low exercise and then running full out again and doing that in several cycles; mixed, where you're doing both moderate and high intensity; and SIT, which you might not hear as often, stands for sprint interval training, which is kind of a funny kind of training where you basically sprint for 20 to 30 seconds at over 100% of what you could sustain because it's only a sprint, and then you just sit down and then you do it again. As you look at this, you can see that the SIT, the sprint interval training, gives you the most benefit as far as efficiency. But the trade-off of this is that because it's a maximum speed sprint faster than you can maintain even for a minute, it's very difficult to get the volume of this. So, you can see that the next group here is combined between high-intensity interval training and mixed. Basically, you need to do high-intensity interval training at about 90% of your maximum heart rate or more in order to get a significant increase in the efficiency of your mitochondria.

So now with these things put together, I have a better idea of what are the components. When they say get 150 minutes of exercise a week, I can more precisely say you should be getting certain components and those components will grow basically linearly over time until you hit 100%. Putting those together, I then went and looked for a training program that would basically go off of the specific components of what I wanted to train for the marathon. For this, I then went for a mixed component where I had one component was high-intensity interval training, so I'd increase the efficiency of my mitochondria; another one that would go for the moderate intensity where I'd be increasing the total number of mitochondria that I have; and then a third one that would treat me what sort of is a tempo pace, what it is like to do a faster pace like I would do in the actual marathon itself.

The less-is-more training, which has been done by the Furman Institute, has exactly that. It's about half the volume of most marathon training programs, but basically every week you do one of each of those runs. You do a long run, long slow distance run, which is going to be over 16 to 32 kilometers or 10 to 20 miles, and then you do another speed work, which is my high-intensity interval training, which I was already doing, so I continued doing that basically as I was before. And then one more, which is the speed run where you're doing tempo work, and that's going to be between 5 and 15 kilometers or between 3 and 10 miles, and that would be done basically as fast as you can. By doing each of these every week, I wanted to know how I was doing against my goal. I wanted to run the marathon in less than three and a half hours. This time target was given to me in a way because I had gone and done a VO2 max test, the full test where you're on a treadmill, and they put a mask on your face, and they tie you to the ceiling in case you fall so you don't fall on the ground when you're going at maximum speed. I ran on that, and they gave me a full accounting of what my VO2 max, the maximum amount of oxygen I could process per minute, was. They gave me an estimate based off of my stats. They said you have a VO2 max of 55. I was quite proud; that's about 1 in 50 level VO2 max. They said we think you could run a marathon in 3 hours and 36 minutes.

At the time, I said great, now I'm not going to run one, but it turns out that I was going to run one. So, setting three and a half hours, I wanted to see how I was doing against that. I used Regal's formula, which is a formula that, given a certain distance and speed, will then estimate how long you could do a longer or shorter distance for. I used that then to estimate how long it would take me to run the various distances and plotted that out every week. Here's what it looks like for my test for that.

[caption id="attachment_3373" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Line graph comparing projected marathon finishing times over 16 weeks for three training methods: Tempo, LSD (Long Slow Distance), and HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training)[/caption]

So, this is then my estimate for each of the 16 weeks of how long I was projected to finish the marathon in. You can see at the beginning, for my tempo runs, I was more around 3 hours and 40 minutes, and then over time I was able to improve my speeds until at the end I was more under 3 hours and 20 minutes or so. Likewise, my long slow distance runs, the one where I was running up to 10 to 20 miles distance, also improved over time, and my high-intensity interval training, my fastest speed, actually had the biggest gain until I was almost looking like I was going to run in three hours. But of course, a marathon is very different than running two minutes at your maximum speed, so I generally looked at my tempo run as the most reliable for this.

This gave me a good feeling that I was improving. I improved about 1% every week for the first 10 weeks, and then I think I kind of plateaued after that. I didn't see as much benefit, but 10% is about two minutes off of my marathon time. So, it's quite material. It took around 20 minutes off or so from the 3:40 down to the 3:20 level.

Then the last hurdle that I had as I was getting ready for the marathon is that marathons are hard. To run a marathon, even in the practicing for the marathon, you might have noticed that in the distances that I talked about, a marathon is 42 kilometers or 26 miles. You never run that distance when you're training for a marathon, which I found to be kind of surprising because it's so long. It's quite exhausting on the body, such that if you were to run that during these 16 weeks, you would basically throw yourself out of being able to train for the next week or two, which is not okay when you only have 16 weeks to practice in. So, I knew that going into the marathon was going to be harder than any distance I had run in the meantime because I was able to run those distances and yet keep on doing the other training.

So, I started to do research on what it is that you need in that last 10 kilometers, so the last four miles of the marathon. If you've talked to someone who's done a marathon or done a marathon yourself, you might be familiar with hitting the wall or bonking. This is where basically you've run, say, three-quarters of the marathon, and then all of a sudden you just feel like you can't go any further. This is where people talk about dropping out or all of a sudden they just need to walk. They can't keep up the pace that they've been able to hold for the entire time or that they did during their training.

So, I did quite a bit of research on this to see what is the cause of this and how do I avoid doing this when I will never have run a marathon before I actually ran the marathon. I came across this study that shows basically the scientific approach compared with freestyle. This is the running velocity that people were able to maintain in each section of the marathon. So, this is the first 5 km, the second 5 km, all the way up to the last 40 to 42 kilometers. The scientific approach is the scientific approach, and the freestyle, do it as you will, is the freestyle. You can see that the scientific approach is able to basically keep the same pace almost through the entire 42 kilometers, whereas the freestyle loses quite a bit after the 30th kilometer.

So this is the running velocity that people were able to maintain in each section of the marathon. So this is the first five kilometers, the second five, all the way up to the last 40 to 42 kilometers. And the scientific approach is SCI and the freestyle, do it as you will, is the FRE.

And you can see that the scientific approach is able to basically keep the same pace almost through the entire 42 kilometers, whereas the freestyle loses quite a bit after the 30th kilometer. So what's the difference between these two approaches? The answer is that the scientific approach is taking a lot of calories during the race itself. The marathon takes around 2000 calories just to run that distance.

And basically people in their stores and their body stores will have around 30 kilometers or so of energy that they can travel. And so it's after that 30th kilometer that you really start to feel like you just don't have the energy to carry on. Go ahead.

Mike - Wait, quick interjection. So because you should be at fat burning throughout the majority after the first five minutes or so of running the marathon, you get an increase in glycogen breakdown after the beginning of, so your blood glucose levels spike. And then as you continue it during your aerobic run and shift to fat burning, then glucose levels start to come down. You start to deplete your glycogen stores in both your muscle and your liver.

And then when they get low enough, I mean, you could have all the fat in the world to burn off. But the fact is, if your glucose levels fall below a certain point in the blood, I don't know if it's 40 milligrams per deciliter, but when they get very low and you just, your body can't sustain glucose output versus how much glycogen and complete glycogen depletion. Now you're completely fried. You're done, you're finished.

I mean, you basically just lay on the floor. You can't do anything until you restore your blood and glycogen levels.

Crissman - Yep. Yeah, and you can see these people like in the freestyle here, you can see after the 30th kilometer, they're basically done. They're hitting the floor. So they finished on average 10 minutes slower than the scientific approach where they were taking gels. And this is not talking about getting a banana at the 20th kilometer. I had practically a bandolier of gels that I ran with. So I had 10 packets of 100 calories.

I went into the race with an extra thousand calories, sorry, yeah, thousand calories in gel as I ran it. And every four kilometers, I would be taking another gel. There can be some indigestion issues with the marathons, but the studies show that basically the increased gel doesn't make that any worse. So while that might be an issue for some people, you're still better to take the gels and avoid bonking the wall than to try and not take them.

In fact, I felt this around kilometer 20, I started to feel a little uneasy. I'm like, okay, my stomach feels a little queasy. Am I gonna have stomach issues? And then I slammed on another gel, it seemed to be fine and carried on. I was able to carry on straight through to the 40th kilometer. I think I dropped from a four or 45 minutes per kilometer to a five minutes per kilometer rate. I lost maybe 20 or 30 seconds on my overall time due to a slight drop in pace, but nowhere near the 10 minutes that I would have hit if I'd hit the wall. Another comment or related topic to this is carb loading. You might have heard this before for marathoners that before they go on a race, that they spend time eating lots of pasta and things. I found a study that talked about this with cyclists and they broke the cyclists into four groups.

And the slowest group was the group that went on a long endurance cycle and they had no breakfast and no calories or gels during the race. And they did the worst. The next group was the group that had breakfast but no gels or calories during the race. They did the next best. And then we had a tie between the two groups that either had gels during the race did the best, regardless of whether they had breakfast or not.

So more so than trying to eat calories in advance of the marathon, it's important to actually take the calories during the marathon and about a thousand or more in order to get yourself across the Smith and Schlein.

Mike - Not just all calories, but sugar. In this case, you need sugar to replenish what your body can't pump out.

Crissman - Sure. Yeah, you wouldn't be able to digest the fat fast enough. Correct.

Mike - Yeah. Yeah. And plus it would weigh you down the digestion. You don't want to digest when you're actively, you know, the energy should be directed towards your muscles, not towards digestion in that case.

Crissman - Exactly. So with this and my training, I went in for another VO2 max test the week before my marathon. And they said that thanks to my training, my VO2 max had gone up to 61.5, which is quite surprising for me. That puts me at about one in 300 people by age and was able to finish it not within the 3 hours and 20 minutes that I had hoped for, but within a respectable 3 hours and 26 minutes, breaking the three and a half hours that I wanted to, putting me just a minute and a half short of qualifying for the Boston Marathon, but that's okay. I don't have any plans to go to Boston at this time. So.

Mike - So wait, so I have a whole bunch of questions. It sounds like you're going to do marathon training again, true or false?

Crissman - I think at this point, no plans.

Mike - No. So I appreciate, so the data -driven scientific approach for how to even go about marathon training, fantastic. So it seems like that process was more exciting for you than the actual process of running the marathon itself.

Crissman - Yeah, the marathon, I mean, it is, anyone who's run it will tell you it's very brutal. I was out for a full two or three weeks afterwards. So after I completed the marathon, coming off of it, there was, I got a hotel right next to the finish line. And so I only had to go maybe, maybe a hundred meters or so. But within that hundred meters, in order to cross over a bridge that was over a river, I had to go up three steps, three stairs.

That was almost as hard as the marathon. At that point, all the adrenaline was gone from trying to do the thing. Just trying to climb those three steps, I was severely disabled for weeks afterwards. Also, yeah.

Mike - Exhausted. Exhausted. Yeah. Still great still great data VO2 max 50 would you say 55 before 63? I mean, it's still fantastic data. So

Crissman - Yeah, 61.5 afterwards.

Mike - 61.5 Yeah, it's fantastic. So yeah, congrats on that.

Crissman - Thanks. Yeah, it had bad effects on my blood work and my liver enzymes. I think I've seen this on one of the Patreon discussions and you're Patreon actually. Someone else mentioned, yeah, when I train for Marathon, all of my liver enzymes, ALT, AST, GGT, also actually go way over the reasonable bounds.

Mike - How soon after the marathon did you blood test?

Crissman - That was actually in the middle of the 16 weeks of training. That wasn't.

Mike - Oh, wow. Yeah. Well, that's just muscle. So the ALT AST can come from the muscle too. So some of that muscle damage, chronic muscle damage. GGT should be liver too, but yeah, that's a

Crissman - So then testosterone was below bound for me, which is atypical. When I've had it tested before, it was fine. So again, the pressure on my body.

Mike - Total testosterone or free? Oh, okay. SHBG, did you measure SHBG in the, no, just free testosterone.

Crissman - Yep, And then also I had a heart stress indicator which told me my heart was stressed. Yes. Correct. But I got the liver enzymes done actually just a month after the marathon and all were back within normal ranges.

Mike - But your training volume probably, how much did you cut your training volume down to?

Crissman - Oh, right back to baseline. That's after actually for the two or three weeks where I couldn't train at all. I was too exhausted. I had trouble sleeping after that because my knees were so painful. They were fine during the marathon, but just the stress on them was so difficult for several days afterwards.

Mike - Yeah. Now imagine that you, your, your knees and hip joints and ankles adapt to that stress in the short term. And then you're like, ah, I'm going to do another one. And then how many years of that pounding can you take before there's hip replacement, knee replacement? I'm not trying to go down, down that road. So what's your training volume now? No running at all? Or what's a...

Crissman - No, I'm back to straight HIIT. So I'll do about two sessions, two half hour long sessions of high intensity interval training a week. And I'm just working from that. My VO2 max, this is not a full test because I don't have a mask on my face nor am I tied to the ceiling. I'm just using my Apple watch though. My VO2 max is still significantly higher than it was when I started. It's a 53. According to my watch, there's a gap of about 10 points between actual and watch.

Mike - So I keep seeing like these 70 year old athletes on my timeline on social media and like running, you know, a hundred meter dash and stuff like that and just looking fantastic. So I've got visions of getting back into hit once I've got the freedom of, you know, freedom of scheduling. Not just that doing, yeah, I'm a big fan of sprints. So even weighted, weighted hit, you know, so putting on a weight vest or some ankle weights and running it with, you know,

Crissman - Huh? Highly recommend it.

Mike - Because you can put resistance on it and improve your speed. So that's how I would do it.

Crissman - Yeah, jump rope, bicycle. Yeah, I mean, there's a lot of variation that you can do to find something that works for you because, yeah.

Mike - That would be the cardiovascular benefit but for the actual sprint you have to get the leg you have to you've got to get the hip extensors You know, you've got because you're lifting your legs, right? It's a power rather than just you know, I'm jumping up and down and it's just plant reflection. It's just your ankles, right? So there are more muscle groups in hip hip hip stuff that you need, you know, so

Crissman - Well, I do remember that you get a higher VO2 max measurement from running than you do on a bicycle, about 10 % to 15 % more, if I remember right. So that's what you're talking about, more activation with just basic running things than you would with sort of sitting on a bicycle, for example, or using legs intensively, but maybe less so of the upper body.

Mike - But you're sitting too, so you don't have to hold the full body weight in that case. Yeah. All right. So should we go through your data? All right. Yeah, let's see. Let's see. Hang on. Share.

Crissman - Yes, absolutely. What have you got? What can you tell me?

Mike - Okay, so we'll start with sleep, right? So for those who don't know, Criss tracked his data, resting heart rate, heart rate variability, slow wave sleep, total sleep, all the things that Whoop provides. This isn't a Whoop specific thing, it's just what Criss wore. I mean, you could generate these data with basically anywhere, Apple Watch, Aura. So not here to promote Whoop, that's not the goal. So when was your marathon training? During which months?

Crissman - It would have been through November 8th through to February 25th.

Mike - Ah, so can you see what I've got? Yeah, yeah, okay, there we go, increasing it, decreasing it. Okay, so it's this whole period then is the marathon training. Ah, okay, all right, so unfortunately there.

Crissman - Yep, It starts out lighter, so, yep, go ahead.

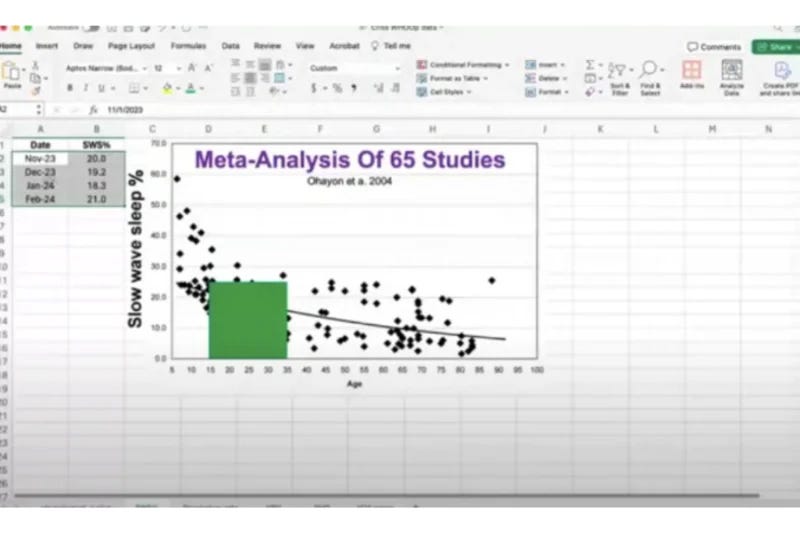

Mike - I was just going to say, unfortunately, there's no before, you know, the five month period before, but it's still okay. I mean, you can pretty much see your slow wave sleep percentage. So that's your deep sleep for those that don't know deep sleep divided by total sleep multiplied by a hundred. Uh, it decreases during aging is shown here. This is a meta analysis of 65 studies, slow wave sleep percentage on the Y axis plotted against age from basically five year olds to 90 year olds. And in youth.

extreme youth, well I don't want to say extreme youth, but very young. You can see that it's about 25%, and the slow wave sleep percentage is about 25%. And then for someone who's around 90, granted it's extrapolation based on one point, but if you go to someone in their 80s, it's somewhere around 8 % of total sleep time. And that's potentially important because slow wave sleep, again deep sleep is linked with Alzheimer's disease risk.

Crissman - Yeah.

Mike - So we want to avoid this age -related decline. So during your marathon training, there wasn't any severe reduction for your percentage of slow -wave sleep, which is good news, because if marathon training starts to mess with slow -wave sleep, sure, you get the cardiovascular health benefits, or potentially, right, but maybe you're increasing risk other places. So you can see it was around 18.3 % to a high of 21%. So what I did was I highlighted that range. So.

And again, I don't know where your data is now or where it was before, but at least for the marathon training period, I mean, it's better than expected, you know, the trend line based on your chronological age. So you'd be somewhere, you know, here in this range, 15 to a 35 year old, which is pretty good news.

Crissman - Mm -hmm.

Crissman - Great. Yeah. Yeah. I was just going to say also that last week, up until the last month, the February month, is probably actually the best baseline representation because there's about a three week reduction in overall intensity. So that's sort of why I think that because as you're getting ready, well, there's the marathon, which is one intense thing. Overall, my training volume was decreasing as I went through the month of February. So I had the benefits of the increased health from having done the previous 12 weeks. But that's probably why that was my highest.

Mike - Did you track training volume in terms of either steps or actually even the, I could look at a correlation for the average daily heart rate as a metric of how active you were on that day against slow wave sleep and we could test the correlation. Is the deloading in February associated with your training volume?

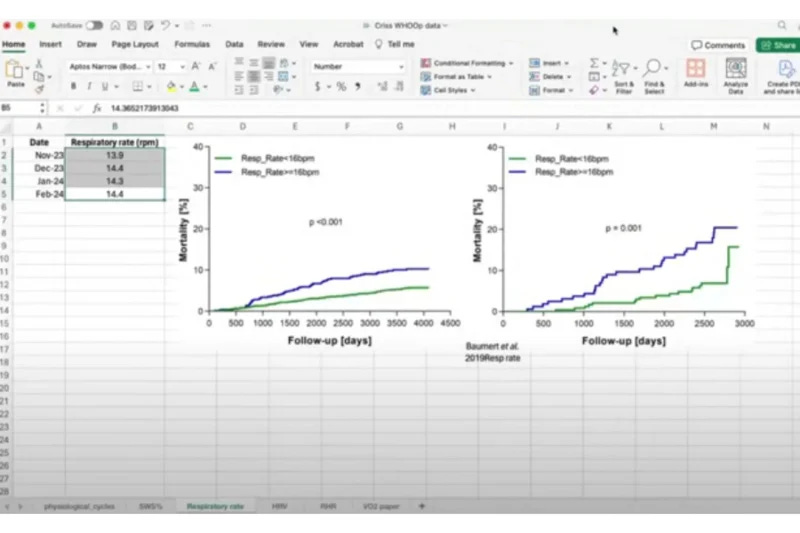

Yeah, but that would be for another day, so then, so another important metric to consider is the nighttime respiratory rate, which is how many breaths per minute do you take while asleep? And there isn't much published data on that in terms of all cause mortality risk, but there is this one study. Granted, it's in, I believe this is, these are two different cohorts. This one is in 70 years olds and this one's in about 80 years olds. So we've got,

[caption id="attachment_3376" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Line graphs that compare mortality rates over days of follow-up for different respiratory rates, annotated with statistical significance markers.[/caption]

How many people died, the rate of mortality percentage, and then their follow -up starting from their initial assessment of their nighttime sleeping respiratory rate. And for people who had a respiratory rate that was less than 16 beats per minute in green in both studies, they had a lower risk of death for all causes compared to greater than 16. Now, could these values be lower in relation to mortality cut points at younger ages? I mean, there's just no published data.

This study was published two or three years ago and there haven't been any follow -ups in other age groups. So hopefully that'll get published at some point. So your respiratory rate comparatively is good with a 16 cutoff, 16 breaths per minute cutoff. You're consistently lower than that. So fantastic news on the nighttime respiratory rate.

Crissman - Right. Did they give a reduction like any hazard risk ratio for that or an estimate based off of the increase or longevity?

Mike - Yeah, I'd have to look at the study. I don't remember off the top of my head, but we can post a study in the, you know, and I can send you the study and you know, yeah, you can, I don't have it mastered, you know, memorized off the top of my head. There's only so much volume that the brain, you know, the Lusk garden brain can. All right, so then heart rate variability, resting heart rate changes over that.

Crissman - Okay, yeah, I'll take a look.

[caption id="attachment_3377" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Chart displaying heart rate variability by age and time of day for males and females, with distinct lines representing each group and time.[/caption]

Mike - Five month period, and what's interesting is with the increase in volume and training volume and even decrease in training volume, there weren't any major shifts in your heart rate variability and even resting heart rate as you'll see, which could suggest over training. I mean, I'd imagine that as your training volume increases, you potentially find an upper limit where your body wouldn't be able to adapt beyond. In my case, that's true, unfortunately, for me.

Gorilla mindset, but physiology that's like, no, that's too much, enough. These data start to suffer. In your case, that doesn't seem to be the case as it's pretty close to a tight range. I've seen data, you know, where heart rate variability will tank into the thirties and then other months it'll be a little bit higher, you know, in the sixties. That's not at all true in your case. So in terms of this range, I've got that highlighted here. So.

Based on chronological age, this study included a thing, nine or eight million people looking at the same WOOP metric that provides HRV, what is it, root mean squared of successive differences. That's the heart rate variability measure that WOOP provides. But using your range, you'd be above the median at any chronological age up until around 30 to 35 years. But you could be within the wide range for basically every age group. So it's hard to say, is this youthful? But it's definitely better than expected age would be somewhere around 40. So throughout the whole period, you're above that, which is good news.

Crissman - Yeah, there's a lot of variability in that. I mean, those are the monthly averages, right? On some days I had heart rate variability over a hundred. And then after the temple runs or some of the other things, sometimes it would be like, I always, when I had the inversion where my resting heart rate is higher than my heart rate variability, I'm like, okay, that was a bit of a tough workout there. The other thing that makes my heart rate variability, perhaps confounds it is that I do go out drinking on the weekends. So I'll have maybe five drinks on the weekend. And that was one of the number one things I found that would just tank my heart rate variability. I consider that to be, and I have no studies or science to back this up. I consider that to be superficial. Like if I went on a long run and my heart rate variability was low and I tried to run the next day, I would feel tired and not quite up. But if I went out with my friends and had, um two pints, I wouldn't notice the next day that I was particularly put out by it or overly stressed. So that's a bit trickier. And it's one of the things why I'm so impressed with your ability to precisely track the heart rate variability every day and try and move the numbers up.

Mike - Wait, so there are a couple of factors going on there. One is when considering that you had days of very high heart rate variability and days of very high resting heart rate, which for those who don't know, that's well, very high heart rate variability would be good, but in the context of a higher resting heart rate, that's going in the wrong direction, but that your data was able to stay pretty tight month to month. That shows that you are able to manage, you know, the chronic overtraining phenotype. So if you're...

After the long, one of the harder days or high volume days, if your heart rate variability was lower and you saw that, then you're like, all right, maybe I've got to do the tempo day or you basically managed it well enough so that you didn't push the needle to the point of the overtrained phenotype being a lower heart rate variability and the higher resting heart rate. So.

You did a great job of managing it there. I mean, that's not an easy thing for most people to manage, you know. And I'm not sure if you did that on purpose or just by feel, but.

Crissman - It's not cleverness on my part aside from the fact that I deliberately chose a training plan that had a lower volume than most marathon training plans. So, a standard marathon training plan will say you should go run six days out of the week. And some of those are kind of casual runs, whatever, but they would have at least twice the volume of what I did.

So that gave me the time then to have my HRV recover back to its height and my resting heart rate to sink down. So as a result of the lower than common practice amount of volume that I did for my running, I think that's what gave why you don't see sort of my heart rate variability dying as the intensity of the exercise went up. Because it was only until January.

The end of January, beginning of February, I was starting to do the really long runs where I do like a 16 kilometer full speed pace, tempo pace, or a 32 or 20 mile, a 32 kilometer, 20 mile run all at once that I started to put the pressure on. But because of the volume overall, I had rest days. I was only doing it three days a week. And I think that's, as opposed to any clever scheduling, probably what enabled my HRV to remain relatively stable.

Mike - But that is somewhat clever scheduling because, you know, I'm sure that there are people out there who are like, I have to do this six days a week to run my marathon. And they push themselves into that overtrained phenotype and don't actually look at the data. So granted you weren't doing it on purpose, but you actually were doing it on purpose, right? All right. So then the other thing too, with the, with the two pints of, uh, whether it's alcohol, right? So, or alcohol based stuff. Yeah. Four drinks. So, maybe it won't affect you as much as, you know, a long run with similar heart rate variability, resting heart rate the next day after drinking. But have you run on those days or done a workout on those days when your heart rate variability is lower, resting heart rate is higher as a result of alcohol the night before? Have you done a workout on the following day? And if so, was it as good as your usual performance? Was it harder to go through your workout on that day or you didn't notice an effect?

Crissman - Don't notice an effect. Yeah, no, I don't. Given my sort of lower volume, right? I mean, running twice a week for half an hour is a serious runner would consider not, you know, warm up. I also don't have the liberty, like when I have my day scheduled, I'm doing my exercise that day. And then I make up for that lack of responsiveness to the HRV by basically having kind of an overall lower volume. So, look, I've had enough time to recover. Today's the day that I have to hit the gym. So I go and hit the gym.

Mike - Yeah. It's that I have exactly the same mindset, but wait with the alcohol in terms of after an alcohol day, the next, Oh, so you're saying after an alcohol day, if the workout was scheduled for the next day, you're doing, you did, you did it no matter what, but your subjective experience of your performance during that day, it, nothing crazy where it's like, ah, this isn't a good workout for me. You know, it doesn't affect you. You're used to it. You've, huh? So in my case, whether it's physiological or placebo, I don't know, but I know that trying to train through below average, whatever my 30 day average or so, heart rate variability, resting heart rate is, it's harder for me to hit my rep goals for compound movements. So pull ups, overhead press, things that require dedicated focus and effort. But that's without alcohol, right? But I'd imagine alcohol would make that.

So it's good that it hasn't negatively affected your physiology. You're able to train through. So anyway, all right. So in terms of, in terms of your resting heart rate, the data is even better there. This is whoops data for, for, um, uh, age related changes in resting heart rate. So average resting heart rate on the Y axis plotted against age 20 to 50 years. So you'd be somewhere around here. How would 51, what are you chronologically? 53. Yeah. Yeah. So you'd be off the list, but, uh, um, Fitbit data shows that it starts to decline after that. Nonetheless, somewhere around here chronologically, you can see that your averages for each month, 48 to 49, which again is fantastic that there isn't a spike during marathon training, that would put you below, you know, super youthful basically. I mean, an average of 54 is what you'd expect to find in a 20 year old. And this is already in a, you know, preselected population, people who are wearing fitness trackers.Generally aren't intending on being sedentary. So you'd be even younger based on quote unquote, or quote unquote younger based on resting heart rate. So fantastic news there.

All right, so what else we got on my list here? Ah, okay, so then we've got VO2 max paper. Yeah, all right. So what's been making the rounds lately is the idea that we want to have VO2 max as high as possible. And there's almost this skew of, you know, we need to be elite endurance athletes to maximize our longevity. And that's in part because of not to name -drop, but Peter Attia And Peter is basically referencing this paper. And this paper will be in the video's description. So if you're interested, check it out. And what they did here was they compared six groups of fitness levels from least fit to extremely fit. They quantified it by METS, which can be translated into VO2 max. So the extremely fit group had a VO2 max of around 51.

Whereas the least fit was 17. So that's our range, 17 least fit to 51 extremely fit. And then when looking at mortality risk, which is shown here, all cause mortality risk, when using the extremely fit group, again, VO2 max of 51 and comparing that against all the other groups, people that had that VO2 max and the least fit of 17 had a four -fold higher risk of death for all causes. So the least fit, four -fold higher risk of death for all causes. So that's the idea that's been circulating that we need to have a VO2 max as high as possible, but I haven't seen Peter mention any numbers. So it's important to put that into context because as you mentioned, your pre -marathon training was 53 or 55.

Crissman - 55

Mike - 55 and this is without I mean what kind of training volume running wise per week?

Crissman - Well, I'm only doing a half an hour, actually two half hour runs per week, but I've been doing it consistently for three or five years. So I think I'm pretty maxed out actually as far as my VO2 max goes. Although I did gain even more once I bumped it up to marathon level training.

Mike - Yeah, but the point there is we don't need four hours or six hours. I mean, you're doing it for an hour and you've got a VO2 max of 50. So I think that's an important point because like I said, the data, the meme that's perpetuated on social media is that we've got to be elite endurance athletes. And from your data, one hour in conjunction with all the other weight training and everything else you're doing, VO2 max over 50, you're in the extremely fit group. So.

The other thing too here is to point out, the extremely fit group, VO2 max of 51, when compared with the high fit group, which had a VO2 max of 42. And I should say, from my own experience, I measured VO2 max, same thing, face mask, the whole thing, a real VO2 max test, not this estimated stuff based on resting heart rate, which is not reliable, or nowhere near as close to reliable. I mean, there are people online who are like my...

My Apple Watch says my resting heart rate is this, my predicted VO2 max is 60. And I'm like, dude, you're 60 years old, there's no way, there's just no way. So when comparing, from my own experience, three VO2 max in the lab, from 2012 to 2017 or 2018, I was in the low 40s each time. Now that's with my regular workouts, my full body 90 minute workout, plus walking, it was 15 to 20 miles per week.

No running at all. So you don't have to be an elite endurance athlete to be in the quote unquote high category for VO2 max. Now is my VO2 max the same since then? I have measured that. I can't say. At worst, I'd imagine I'm in the fit group, but who knows? I'd have to measure it. The interesting factor here is that VO2 max is milliliters of oxygen consumed per kg body weight. So I'm 20 pounds lighter or 15 pounds lighter.

Then I reduced the denominator. So assuming my maximum ability to consume oxygen hasn't changed, or even if it has changed, with the lower cardio training volume, I'm not walking 15 to 20 miles a week anymore on purpose, I find it hard to believe that it would be dramatically different. But all right, nonetheless, comparing the 51 VO2 max versus the 40, 42, you can see that even having high fitness, 39% increased risk of death relative to the highest fit group. Okay, so that's big news. I mean, that's basically saying you want to have your VO2 max above 50 relative to the 40s, right? And to put that into further perspective, you know, people who had CKD, chronic kidney disease, 49% increased risk of death. So, you know, being high fit is almost as bad as having CKD relative to someone who's extremely fit with a VO2 max of 51. So this is pretty astounding data.

Right? But there is some devil in the details. And this brings us to the mortality risk across fitness categories according to age groups. So this study included a very wide age range from 30 year olds all the way up to 90 year olds. And you can see the sample sizes for each. They're very large sample sizes, which is great news. And then comparing at each age group, getting all the way up to 80 to 95 years, from least fit to extremely fit. And now the referent is defined as the people who are the least fit, VO2 max of about 17. So again, once again, within every group, if your VO2 max was, what was it, 51, around 51 in the extremely fit group, you had an 84 % chance lower risk of all -cause mortality for 30 to 49 year olds, 78%, 80%, 66%, 73 % reduced relative to the least fit group.

But, where the details start to become interesting, at least for me, is when you look at the highly fit group and see the extremely fit group, okay, now it's only a 10 % difference in terms of lower risk. Now granted, 10 % is still a big deal. I don't want to throw away any association for reducing mortality risk, but this idea that the 40s versus the 50s in VO2 max is this dramatic reduction, maybe as bad as CKD or other smoking.

It's kind of overblown. I mean here for 50 to 59 year olds there is only a 6 % difference for the VO2 max of 42 versus the 51.8 % for the 60 to 69 year olds, 13 % and okay, 15%. But where the story gets a bit more interesting is, you know, when considering that the 50 group has the lowest all cause mortality risk at every age range and is even better than the high -fake group in terms of all -cause mortality risk, then the expectation is, well, you must live to 115 years, or 120, you must get to the maximum lifespan, your VO2 max is 50, you're gonna get to the max lifespan. What's your life expectancy if you have a VO2 max of greater than 50? So they looked at that, and here it was men with peak exercise capacity of 10 to 12 meds. That's a VO2 max of 35 to 43. So this is not actually looking at the greater than 50.

So the fit and the highly fit, they only live four and a half years longer compared to the lowest fit. The people who had a VO2 max of 17, I mean that's a five year increase in average life expectancy. And those with the extremely fit, higher than 51 VO2 max, had a six year. This isn't 25 years, this is going from 73 to 79 years, right? So one thing I'm always talking about is how we can do better than the eat real food and exercise approach? A VO2 max of 50 is great, but if you're telling me I'm only gonna expect to live to 80, that's just not good enough. Can we titrate the exercise dose? Can we look at biomarkers of overtraining? Can we look at blood biomarkers to make sure our liver, as you saw, isn't chronically damaged or muscle damaged? All right, so what about for the women?

So the story is about the same. In this case, the 10 to 11 and a half METs, so that's a VO2 max of 35 to 40, they lived only two and a half years longer than the lowest fit group, which is outrageous. I mean, their VO2 max is double. And if we only go by, you want to have a VO2 max as high as possible, I mean, that's only a two and a half year longer life expectancy. And I'm not trying to diminish that.

It's important. I just want to add context to what's already out there. And then for the highest, for the highest fit group, just to finish it off real quick, for the highest fit group, it was about seven years. But again, this is going from a life expectancy of 69 years and lowest fit to 76. Again, not 95, not 115. So.

Crissman - Right. So I agree with your point and I think that as you brought up, one of the more important things to look at is that this is divided by your body mass, your weight. So this isn't one indicator of how your lung capacity is or your mitochondria is because as soon as you divide it by the weight, that can overwhelm things. If you're on the heavy side, then even if your lung performance is above average, if your weight is

greater than that, you're not going to be in the elite and the other elite despite the fact that you could have quite a good cardio respiratory system. In some ways, I feel like this is... They talk about it being as fit as possible, but in some ways, I feel that what they're really saying is that it's important to keep a low BMI overall.

Mike - So that's an interesting point because I should have brought up the demographics, the subject demographics in the paper. And it was the average BMI within groups, within each age group was overweight or obese. What that means is a BMI of 25 to 30 is considered overweight. And actually, if I remember correctly, the BMI for each group was closer to 28, 29, 30 in each age group. So these were overweight people.

And then in some cases it was an average BMI of 30 or more, which is clinically defined as obese. So, but what that says is for this paper is if you are overweight or obese and can attain a VO2 max of greater than 50, you will still have the lowest risk of all -cause mortality. But their models were adjusted for age, sex, BMI. But what you're raising is the more interesting point of what if your BMI was lean?

and you have the B amount, the VO2 max greater than 50, what's the life expectancy gain there? And I didn't see that as a subset. I wish they did, but now that population is unfortunately probably very small. We're talking about a very, very small group in terms of maybe hundreds, not 20 or 30 ,000 that they had in each of these age groups. So just to finish off too with the people who are older than 70 with a cardiorespiratory fitness greater than seven METs, which is a VO2 max of 25.

They only lived about three years longer compared to the lowest fit group. So again, you know, this idea of, uh, you know, granted that my goal is to be as fit as possible, not just, you know, strength and mobility balance, but also VO2 max. This is only a two, a three year gain in life expectancy. You know, they lived to 87 years on average versus 85 years. So, um, so I think it's important to frame the context of, you know, what, what Peter's putting out there, uh, you know, that.

VO2 max is an important component, but I think we need more specific markers. It isn't just, you know, eating real food and exercise, to get good sleep. It's how can we, you know, get the exercise prescription and get the dietary prescription and, you know, look at biomarkers of organ and systemic function to really push us beyond these 87 and 95 years, you know, caps for life expectancy and studies.

Crissman - I mean, I'd add to that, play the long game on this. When you're going for longevity, it's easy to, if you're trying to maximize VO2 or your VO2 max right now this month, unless you have a race coming up or like a marathon, you can take your time on it. And over time, even if you're starting at a standard level, if you're continuing to practice it on a weekly basis, eventually you'll find yourself in the extremely fit group. It sort of time takes its toll and you're able to reduce the normal losses you just age from in a sedentary fashion.

Mike - So what do you think about, I agree 100%, I have a couple of factors too. What do you think about the exercise dose that maximizes not just VO2 max, but general fitness, while also attempting to optimize heart rate variability and resting heart rate? In other words, high HRV, low resting heart rate, looking for that dose that maximizes all three, where I think most people are only focused on how high can I get my VO2 max and if my heart rate variability and resting heart rate looks over trained and aged relative to my chronological age, who cares, right? So what do you think about that combination as an exercise prescription?

Crissman - So I keep it minimal. I'm always trying to get the most benefit for the least amount of effort. So my aerobic exercise, despite being quite fit, I'm very consistent. So I virtually never miss even a week of exercising. But just the two half an hour sessions of doing running, I find enough to keep the VO2 max as long as it's on a really consistent basis.

If you take like a month off, then all of a sudden, then the low dose doesn't work because it will take you too long to catch back up to where you were. And then if you lose another month, then now you're basically, you're almost untrained. A study that I looked at that did VO2 max training had basically a 12 week washout period to basically return the person, their cardiorespiratory fitness back to baseline, as if they had never done any exercise at a hall.

So even before three months or 12 weeks of resting, even if you're taking like two or three weeks, I think that if you're combining it with a low regular dosage it is going to be a problem. But if you're able to be consistent in it, then you can use that to optimize both your HRV and high and your resting heart rate low, by only doing a little bit of exercise each week. I actually find that on my exercise days, because it's half an hour, I know that your routines are usually more on an hour or so, if I remember correctly. There you go, an hour and a half. So I don't even notice an impact on my HRV or resting heart rate the day after I do those exercises. In fact, those are some of my better days because they're combined with my fasting and other things. So I think the key to working all those dials, is to find a very efficient thing and then get the most benefit out of doing the least effort on it and then be consistent about it.

Mike - Yeah, cool. Consistency is definitely king when it comes to fitness, but actually any activity, you can make the same argument about fasting or calorie intake, right? If you're better at hitting a certain calorie goal, like I hate to say put it in a loop, but it'll be easier or should be easier because you've been doing it for so long where if you do fall off, it should be easier to go back, right? So, all right. So then the other aspect too is there's a training dose that's not just involving HIIT and cardio.If that's a part of not just your approach, but others approach, if the approach is exclusively focused on cardio and, you know, not on attenuating strength losses during aging or flexibility losses during aging. So if you're spending all of your time dominated by marathon type training, maybe one wouldn't have the time or energy to put into these other aspects of fitness that decline during aging. So for me, it's how can I get the cardiovascular benefit from my 90 minute workouts while also training, you know, mobility, balance, flexibility to make sure I'm, you know, when I'm 80, 90, 100, I'm mobile and look like a young person relative to, you know, my chronological age.

Crissman - Yeah, the other aspects, the balance is one that I also follow with. So I balance things kind of leaning against comfort, I guess. So I still put on my shoes and socks while standing up on one foot, brush my teeth with my eyes closed in the tree pose and my yoga tree pose. Okay. Using my hand for that. Just making sure that you're trying to fight against that sort of normal loss of getting, well, just kind of sit down or whatever. The flexibility I usually work on through weightlifting, you can get good flexibility by doing squats and deadlifts will work the hamstring structure very well. So I keep that up.

But I agree, it's gotta be, you've gotta make sure that you're kind of hitting across the panel. I have some friends who are very intense on the aerobic and then we'll do something like, climb a small hill or something and because they haven't been doing any of the deadlifts or the squats or things and they have the lungs to handle it but sort of the exhaustion of the amount of effort they have to put into it they get tired much more quickly for the effort because they haven't got the muscles to back it up.

Mike - Yeah. So my 15 year old, when she puts on her shoes, is constantly banging into the walls, you know, you would, because she, her balance is terrible. She doesn't train for it. So even at any age, if you're not training it, I do the same thing, you know, on one foot, put the sock and the shoe on. I do that every day. You know, it's so, uh, but that's only a small part of it, but yeah, it's important. I think most people neglect it and then it's, Oh no, look, I don't have good balance, you know, and the hit hit helps with that stuff too, because you know, lifting one leg and accelerating and pushing forward, I mean, you have to have balance in order to do that, you know, to sprint. So that helps too.

So I think we covered it all, Criss. I think we covered it all. What do you think?

Crissman - Yeah, I think that's good. Yeah, I'm really happy to have done the marathon. Thanks for giving me a chance to kind of tell my tale and where that stuff comes from. And we're very much on the same page as far as kind of working the full picture of working through both making sure that you're getting the right amount of exercise, but also watching sort of your measurements so that you don't overstress yourself at the same time.

Mike - Definitely. Cool. All right. Thanks, Criss. Until next time.

Crissman - All right, thanks a lot. All right, later.

Mike - Bye. Bye. All right.