Sub-3:30 in my First Marathon

Science for speed with half the normal running time

I didn't expect to run a marathon. Aside from doing half-hour High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), I don't run regularly, and it always seemed like running a marathon would be a long, painful experience that I didn't need to do. In 2022 summer, I took a V̇O2max test to check my cardiovascular fitness. The clinic specialized in marathon training, and they said that given my high V̇O2max of 55 ml/min/kg, lactate threshold, and running economy, I should be able to run a marathon in about 3:34.

"Great!" I thought. "Now I don't have actually to do one. I'll just tell people how fast I would be if I did."

But, when some friends told me they would run in the Osaka Marathon, I decided it was time to test that estimate and find out what I could do in an extreme endurance test.

Marathon Preparation

So, I signed up and started looking for marathon shoes. Since Nike created the carbon fiber-powered Vaporfly in 2017, shoes have had an even more competitive advantage, allegedly giving a 4% increase in speed. The marathon shoe recommendation sites were confusing and inconsistent. I checked what shoes the top 20 finishers in the last Boston Marathon and found the majority wore Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3s. I bought two pairs—one to wear out training and one for the race.

Choosing a Training Plan

My next thought was, how can I do the least running while still achieving a good time? The common wisdom for preparing for a marathon is, "Run lots." If you're not as fast as you'd like, "Run more."

Common wisdom is often a good starting point. Breaking down common wisdom to the next level and quantifying the benefits by components enables efficiency improvements. I've done this for "eat plant-based foods" and "get 150 hours of physical exercise" recommendations for longevity. Running a marathon was a chance to do a similar analysis for marathon training.

Hazard Ratios are excellent for evaluating longevity interventions but not so helpful in assessing marathon training plans, which have nearly a 100% survival rate. (Phew!) Instead, I turned to V̇O2max, a measure of cardiovascular fitness, for the metric to develop my training plan.

My previous research on physical activities found that different intensity levels provide different health benefits. The same is true for the effects of running on V̇O2max. In a study of various training marathon programs—high volume of slow runs, mid-aerobic lactate threshold runs, High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), and polarized training with both high volume and HIIT—the polarized training provided the most benefit, with high amounts of long, slow distance runs combined with HIIT1.

Now that I had a study-backed approach, the next step was to make a training plan. An Internet search showed many plans, although most focused on daily runs, with maybe one weekly rest day. That was a higher time commitment than I wanted, so I searched for lower mileage plans and found the FIRST, Less is More program.

The basic approach of three fundamental runs weekly—long, slow distance, HIIT, and tempo—is excellent. Since I have been doing HIIT for years, I kept one of my weekly runs as my regular HIIT instead of doing the FIRST speedwork trials.

I ran at the fastest pace I could for the distance for the tempo runs, also called threshold runs. Initially, I couldn't match the target time from the FIRST plan. A few weeks later, I could reliably outrun it.

The long, slow distance (LSD) runs are for building distance endurance and are deliberately run at a slower pace, about a minute slower per mile (40 seconds/km) than my 10k pace. These runs gradually increased in distance from 10 to 20 miles (16km to 32km) and quickly became the most draining runs of my week. I could do useful work after running an 8-mile (13km) tempo run, but a two to three-hour LSD run would exhaust me well into the next day, as even my walking pace fell to a half-speed hobble.

Tracking Progress

With three different kinds of runs weekly, I wanted to know if my speed was increasing. To compare the different distances, even within the same type of run, I used Riegel's Formula to predict my marathon time based on the distance and duration of my runs. As you might expect, the longer the run, the slower the pace, and Riegel's Formula fits this speed change for most runners in the formula:

New time = old time X (new distance / old distance) ^ 1.06

For example, when I ran ten miles in 71 minutes, that gave a marathon projected time of 71 X (26.2/10) ^ 1.06 = 197 minutes, or 3:17.

Charting my projected marathon times against the training week helped me visualize my progress. I improved my projected time by about 1% per week during the first ten weeks, although I leveled off for the last six.

Boosting V̇O2 max

Even before my training, my V̇O2 max was at the 98th percentile by age2. One probable cause of my high V̇O2 max is my sauna habit, which increases V̇O2 max gains by over 40% when done after aerobic exercise3. The additional weekly run increased my sauna frequency from three to four times. Although I spent less than 50 hours running during my 16 weeks of training, I spent another 16 hours in the sauna from the four weekly 15-minute sessions. I found sauna time after runs more practical than adding run days.

If it's challenging to get to a sauna after running, some studies have shown that 15 minutes in a sauna suit, a plasticky hooded suit that holds in sweat, or even a hot bath also provide additional V̇O2 max gains4.

Another V̇O2 max gain accelerator is training while fasting. Doing aerobic exercise while fasting (in this study, just before eating breakfast) increases the V̇O2 max exercise gains by nearly four-fold5. I've been doing 5:2 fasting, taking under 500 calories two days weekly, for over a decade. Since fasting days give me some free time from dealing with food, I use those days for HIIT training. Doing HIIT and tempo runs while fasting and the sauna afterward increased the V̇O2 max benefit from the runs.

Marathon Challenges

The 26.2-mile (42.2km) marathon distance is brutal on the body. Unlike other races, it's recommended against running the marathon distance while training because recovery time could cause missing or poor performance on the following training runs. Since I knew I'd be testing a new distance on race days, I researched the common marathon challenges to be sure I was ready.

Bonking

Since I wouldn't be running the marathon distance beforehand, my most significant concern was what would happen once I passed the longest distance I'd ever run. There are many stories of people running on pace only to "bonk" or "hit the wall" near the end of the marathon. In the last quarter, they ran out of energy, and their legs felt wooden or heavy as their pace fell.

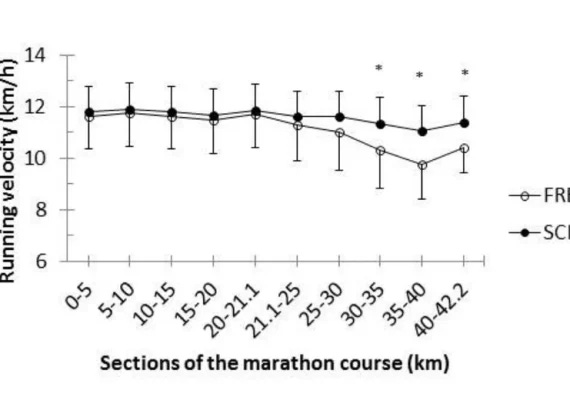

While researching why this happened, I found a brilliant study that tracked the performance of a group of 28 runners through the 2013 Copenhagen Marathon6. Half of the runners could take as many carbs during the race as they wanted (the Freely Chosen branch). The other half took over 60g of carbohydrates hourly (the Scientific Method). The runners following the 60g hourly intake plan fared better in the marathon, improving their predicted times by eleven minutes (a 5% speed increase) compared with the Freely Chosen Branch. Importantly, all that benefit came in the last quarter of the marathon, where bonking becomes a challenge.

Note that the Freely Chosen runners were not avoiding carbs. They took an average of 38g of carbohydrates per hour but needed 70% more to match the 65g hourly of the Scientific Method runners.

For the scientists writing the study, it's obvious that inadequate carbohydrate intake is the primary cause of bonking, and they are baffled as to why many runners don't take enough. You can almost hear their tears in the Practical Perspectives section: "It is unknown why non-elite runners apparently ingest too little carbohydrate during marathon races..."

Carb Loading

It's common to hear about carb loading before a marathon, which focuses on carbohydrate consumption to cram more sugar into the muscles to use during the race. Three to four days of 1g of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight is often recommended. Still, I couldn't find any studies that showed marathon performance benefits from that intake level. The closest was a study of a university course where the students ran a marathon at the end of their class and carefully tracked their macro intake in their diet in the days before7. There was a benefit for high total calorie intake the day before and high carbohydrate intake the morning of, but even taken together, it was a minor factor in the overall variance.

A bicycling endurance study compared the effect of skipping breakfast with taking carbohydrates in a two-hour ride. They found that the worst results, as you would expect, were from the group that skipped breakfast and took no carbohydrates during the race. The next fastest group was the ones who had breakfast but no in-race carbohydrates, and the fastest by 9% was the group that had in-race carbohydrates, with no statistical difference in whether or not they ate breakfast8. It appears the most critical action is to provide sufficient carbs to your body during the race rather than trying to store them in advance.

Cramping

During a long endurance event like a marathon, runners lose electrolytes from sweating. If the electrolytes are not replenished, this can cause cramping, which can be debilitating during a long run. Fortunately, most gels and sports drinks contain sufficient electrolytes to cover this. If taking your own special carbohydrate recipe—a friend made honey pouches—add some salt or take salt tablets with water to avoid cramping.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Nausea, reflux, an urgent need to poop, or other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are other issues that can afflict marathoners. Contrary to expectations, this doesn't seem to be caused by carbohydrate intake. The study above found that the runners taking over 60g hourly had no worse GI symptoms than others. I noticed this myself during the marathon. Around the halfway point, I started to feel some nausea and feared it would get worse. Two kilometers later, I ate a gel and found the nausea disappeared.

GI Symptoms will generally show up before training. I noticed that eating too close to race time would bother me, so I made sure to eat the recommended three hours before my LSD runs and the marathon itself. Since getting gels or other carbohydrates during the race is crucial to avoiding bonking, getting used to your in-race carbs before the race is essential. During the race, I took ten Maurten gels, but to get used to them beforehand, I ate twenty of them as practice during my LSD runs.

Another standard recommendation is to avoid fiber and high amounts of fat the day or two before the marathon. Running jostles the digestive system, which can cause issues not seen in other sports. Triathletes report having the most problems with the running portion9.

Pacing

Marathons are exciting! After weeks of training, when the marathon day arrives, many runners get caught up in the fun and bolt off the starting line at their 10km pace. That doesn't hold up well after the first quarter of the race. Since I had been using Riegel's Formula to project my finishing time from my tempo runs, I hoped to finish in about 3:20. Calculating backward meant I should run at a 7:36/mile (4:45/km) pace. I set my Apple Watch to alert me when I was 9 seconds/mile (5 sec./km) or more from that pace. I glanced at my watch each time it alerted me, and I was often wrong about whether I was going too fast or slow.

Marathon Day

After sixteen weeks of training, it was time for the marathon. The week before, I returned to the running clinic to retest my V̇O2 max, which had gone up to 61.5 ml/min/kg, or 99.7th percentile! They also said my running economy and lactate threshold had worsened, so my new predicted finish time was 3:36 or two minutes slower. Since those last two factors are more random from test to test, I ignored them and headed to Osaka. I arrived two days early to get the lay of the land and ensure I could get the high-carb breakfast I wanted—three pieces of white toast with honey, a banana, and two lattes. I picked a nice hotel next to the start/finish lines to avoid morning travel.

A standard marathon advice is, "Nothing new on race day." (Aside from the marathon distance!) After making sure that I'd tried everything planned for the marathon—shoes, gels, watch, clothes, pace—the marathon itself felt like another long Sunday run... that went on 25% longer than I'd ever run.

Watch Battery Dying

I was within a few seconds of my pace for most of the race, dutifully following my Apple Watch's pace alerts. Then, after three hours of running, the battery on my watch died. Looking at its black face, I realized I would be in the dark for the rest of the race on my pace, how long I'd been running, or even how much further I had to go unless I saw one of the distance signs. I'd charged it in the morning, but the race tracking and location sharing must have been too much. At that point, I was running as fast as I could anyway, leaving nothing to spare. This all-out final effort was... about 5% slower than before. Ah well. Most of the marathon was done, so I lost less than a minute of time.

My final time was 3:26:24, beating my 3:30 goal and putting me at about the 90th percentile of marathon runners by age. I missed the qualifying time for the Boston Marathon by a little over a minute, but it doesn't matter. The marathon was fun for a challenge and to confirm that the numbers from my exercise routines were convertible into real-world results.

Marathons and Longevity

I had my annual physical midway through my training. My liver enzymes (AST, ALT, GGT), free testosterone, and heart stress (NT-proBNP) test results were the worst they've ever been. Other marathoners have reported similar issues. As a one-off or occasional effort, a marathon is a worthwhile endeavor that can sharpen habits and overall fitness. If running marathons more often, offset the wear from frequent running with healthy food and habits from unaging.com.

Update: A blood test three weeks after the marathon shows biomarkers back in the standard range, so no lasting harm was done. All's well!

Ready to Hack Your Lifestyle and Live Longer? Subscribe Now and start your journey to a longer, healthier life!

Discover your true biological age with our FREE Longevity Calculator and unlock personalized biohacks to optimize your health and well-being.